LGSM News

It's quite illogical to say ‘I’m gay and I’m into defending the gay community but I don’t care about anything else.’ It’s important that if you're defending communities, you’re defending all communities and not just one.

Mark Ashton

It's quite illogical to say ‘I’m gay and I’m into defending the gay community but I don’t care about anything else.’ It’s important that if you're defending communities, you’re defending all communities and not just one.

Mark Ashton

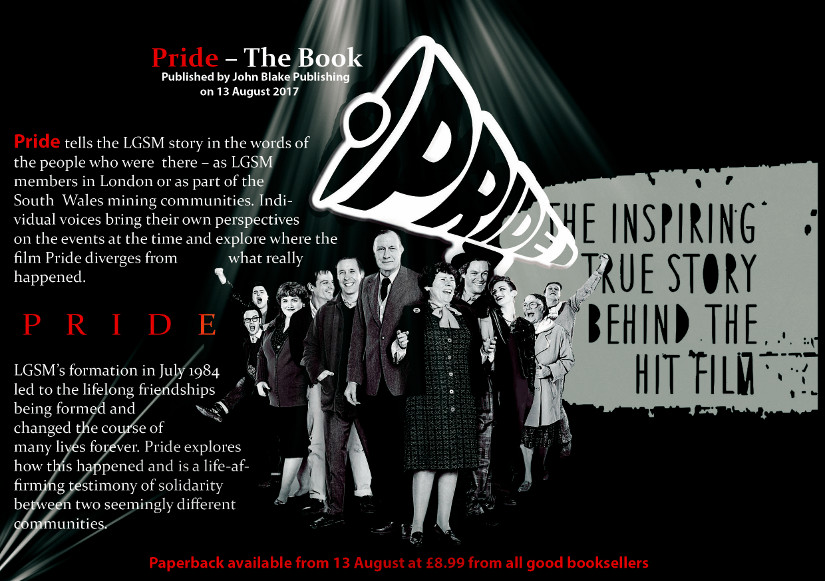

The book that tells the LGSM story, Pride, by Tim Tate, is set to release on Thursday 10 August 2017. It is published in paperback by John Blake Publishing and costs £8.99.

Tim is an author and investigative journalist and has done a fantastic job of presenting our story in our own words, providing an introduction and background text on the historical events of the time alongside the interview text.

Fourteen members of LGSM and/or Lesbians Against Pit Closures (LAPC) were interviewed, as well as five of the surviving key players in South Wales. Each contributor provides information on their respective backgrounds and the experiences and events that contributed towards their part in our story. Tim interweaves the interviews of each contributor to tell the real story in the words of those who were there at the time.

Pride the film does a wonderful job of telling our story, and LGSM owe a huge debt of gratitude to the film’s writer, Stephen Beresford, Pathé, the producers and director and the stellar cast that brought our story to life in such a touching, inspiring and funny way. It is true that the film was firmly and deliberately aimed at a mainstream audience and its reach went way beyond audiences that would instinctively relate to our story. The film introduces fictionalised characters and events without departing from the central events that form our year of existence in 1984-85. It exaggerates some elements of the story in a very sympathetic way for comedic effect, but it stays faithful throughout.

There are undeniably casualties of the film’s mainstream focus, however. The politics and relationships that brought us all together at that moment in time are in large part absent. And although the women of the valleys are given a fair crack of the whip in being portrayed as a central part of our story, the women of LAPC and LGSM were arguably treated less fairly, with the exception of Steph.

With our politics largely absent from the film’s story, you could be forgiven for thinking that LGSM was a personality cult, with Mark at its fulcrum. Mark was undeniably charismatic and driven, but not even he could pull that off! The film also leaves a huge question mark hanging over why we formed and what we hoped to achieve. Our motivations were significantly deeper than “they’re going through what we’ve been going through”, as Mark vocalises in one of the early scenes.

Pride the book takes the story one step further – it explores the motivations and perceptions of many, but not all, of the people that were there. And there are conflicting and contradictory voices, at times – members of LGSM and LAPC did not always speak with one voice, as you will discover.

There are fascinating, funny and sometimes touching or poetic insights into the past and present (a 1984 present, that is) of those interviewed. Here, LGSM’s Brett Haran talks about his family life as a child:

I once asked Mum what Dad’s job was. She told me he was a ‘fret worker’: he worked for one week and fretted for the next three.

Here, Hefina’s daughter Jayne, 16 years old at the time of the strike, perfectly summarises her feelings about growing up in Dulais:

Growing up, the community did feel quite insular to me … Onllwyn is very small: there are only two streets in the village itself. When you stand in the villages of Onllwyn and Seven Sisters and you look around you, there’s a mountain everywhere you look so you don’t see beyond that …. You did feel, however, that you were embraced by Wales and the land.

Here, LGSM’s Ray Goodspeed relates the prevailing attitude within large parts of the mainstream lesbian and gay community to the liberation struggles the LGBT community faced in the early 1980s:

I was even thrown out – ejected – from a gay pub in (London’s) East End for handing out Gay Pride leaflets. They didn’t want to cause trouble: I was told that, if we gays just kept quiet, the police and the government would leave us alone.

And here, LGSM’s Mike Jackson on his personal impressions of Mark Ashton at the time:

And here, LGSM’s Mike Jackson on his personal impressions of Mark Ashton at the time:

Mark was working as a kitchen porter in a hospital at the time. Although he was passionate about his politics, he could suddenly switch to humour and he was also so mischievous. At one point he had worked at the Kings Cross Conservative Club in full drag for six months.

LGSM’s first meeting took place in July 1984 in Mark’s flat on a (now demolished) council estate at the Elephant & Castle, in South London. Eleven people attended that first meeting and numbers steadily grew as each week of the strike passed. We outgrew the meeting room we secured at the GLC’s County Hall, then the meeting space at Gay’s The Word Bookshop, and ended our days in a large upstairs room at an Islington gay pub called The Fallen Angel. Over 60 people were active in the group, rather than the 10 or so portrayed in the film.

Whilst women members were in the minority in LGSM, Steph was never the only “L” in LGSM. And not all LGSM’s women left when LAPC formed, leaving Steph alone carrying the “L” end of our banner on picket lines and demos.

Here, LGSM’s Dave Lewis relates a story of support for LGSM’s work that bordered on bullying and intimidation (in a good way):

I used to collect at a pub called The Union Tavern…. I’d get something like £4 … Lily Savage used to perform there twice a week: she was very supportive of the miners’ cause on stage and would often talk about it in character to the audience. Paul O’Grady … had seen me shaking the bucket outside a couple of times: he always gave money… but could see that the collections weren’t raising a huge amount. And so on two or three occasions, he wouldn’t let anyone leave the bar until they put money in the bucket. And the collection went from four quid to twenty-five quid… because everyone was absolutely terrified of Lily. I certainly was: there weren’t that many things that frightened me then but Lily Savage was one of them.

And was there any truth in the film’s caricature that LGSM brought vegetarianism to the valleys? Here, Christine Powell, one of the reception committee awaiting our arrival in South Wales relates:

They told me that they were vegetarian, and I thought, ‘You may be gay and I can handle that, but what the heck do I do with a vegetarian?’ Eventually, I asked, ‘Do you eat egg and chips?’ And thankfully, they did – because that’s all I could manage.

On the impression that the film gives of the culture clash between LGSM and the South Wales mining communities, LGSM’s Clive Bradley has this to say:

It’s important to realise that the transformative power of LGSM wasn’t just in one direction. It wasn’t just a case of these worthy cosmopolitan Londoners bringing pasta and opera to the remote valleys…. I think there’s a very great danger of imagining that the miners were politically ignorant and needed us to enlighten them. These were communities that had generations of miners who had a radical tradition – they’d been involved in the General Strike – and they didn’t need lefties from London to tell them about all this stuff.

Dai Donovan relates this of the first meeting at Onllwyn Miners Welfare Club when LGSM visited in October 1984:

I’ve heard that some people said to them, ‘Well, who’s the wife and who’s the husband?’ Well, if somebody had said that near me, I’d have f***ing clipped them around the ear.

This scene is played out in Pride the film between Gail, Ray and Reggie. To this day, we’re not 100% sure if this really happened though.

Mike Jackson reflects further on this first meeting:

What was so wonderful for me on that very first visit was that all these people knew about us was that we were lesbians and gay men, and we supported them in their strike. All I ever wanted was acceptance, and here it was, in bucketloads, in this Welsh miners’ welfare club.

Brett Haran again, on his impressions from that first visit to Dulais:

As the mini-buses made their way out of the Dulais Valley on the Sunday evening, the twenty-seven LGSM members inside were filled with a profound respect for the women and men of the South Wales coalfield and a renewed determination to support their struggle against the forces trying to starve them into submission.

And what of that van that had an LGSM dedication on the door? How was this received as it wound its way around the valleys in early 1985? Sian James recounts her memories here:

And what of that van that had an LGSM dedication on the door? How was this received as it wound its way around the valleys in early 1985? Sian James recounts her memories here:

You’d be going past someone and you’d wind the window down and he would say, ‘Are you lesbians?’ And we’d say, ‘Yeah! Are you coming with us?’ Now that person would go home and say, ‘There was a van down in Treorchy today and it was all painted up with a pink triangle….

So, were LGSM responsible in large part for many of the freedoms we all enjoy today, as the film implies? Mike Jackson has this to say on the subject:

… there’s a great danger of LGSM being over-egged, as if we were responsible for everything, which would be a travesty because there were people beavering away in the Labour and trades-union movements decades before us. Really, we were a part of a continuum of activists, but I do think we helped accelerate that gradual process of change.

On reading Pride, you will undeniably get a deeper insight into our story, but there are several key voices missing. Mark Ashton did die in 1987, as the film portrays, and several other LGSM members died very young – among them Derek Hughes, Polly Vittorini, Roddy Barnes, Andy Crabb and Bernie O’Connor. In Wales, both Hefina Headon and Cliff Grist died before the film’s release. We hope that we have done justice to their respective contributions in the story the book presents.